Let’s start from the end: We finally have solved that problem we have been working on for a while. How did we do it? Rationally, first we made sense of the problem-situation. Then to understand that situation we learnt new knowledge, made decisions, and sought for relevant information, until we identified an appropriate solution and then presented it to the client/boss/etc. But at the same time, while going through that process, we have gone through various emotional states too, which probably we haven’t stopped to think about. This affective experience (Kuhlthau, 1991, 1999) had a strong influence on how we constructed the required knowledge, made decisions and explored information.

Knowledge is constructed by combining new acquired information with previous experiences. During our learning process we filter and select the information that is more closely related to what we already know because of our limited capacity to form new meaning. We only seek for information when our knowledge is not enough to solve a problem. Otherwise, we tend to rely on our internal knowledge rather than looking for external sources of information. However, the complexity of current problems are increasingly demanding a need for more specialised knowledge, making almost an essential requisite to broader our learning beyond internal channels.

But reason and critical thinking alone cannot fully solve problems. When we are solving a problem our feelings, thoughts and actions are tightly intertwined; each of them having a key role in that process. Kuhlthau (1991) describes those three as the key component types involved in the problem-solving process and common to each stage: “the affective (feelings), the cognitive (thoughts), and the physical (actions).” The process implies constant iteration of “exploration and formulation, inquiry and inspiration” (Kuhlthau, 1991).

In previous posts (here and here), thoughts and actions of the problem-solving process have been discussed. This post pays mostly attention to the emotions involved in that process, instead.

Feelings and emotions

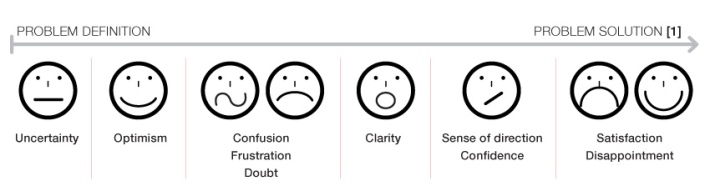

Solving a problem is not a sequential process, although sometimes for the sake of clarity we tend to construct a linear action plan. With often blurred boundaries, research, development, evaluation, and refinement are the main stages of the process. Most of the time we tend to move to the next stage while still completing something from the previous one. In other cases, we could even find THE missing link the night before the final decision needs to be made. While we move (forwards and backwards) through each stage our feelings vary too. Although each of us may have different emotional responses to a same situation, when we are dealing with problem-solving, we all experience common feelings and emotions at similar moments of the process (Kuhlthau, 1991). Most common feelings and emotions are discussed below while situated within the process stages:

Uncertainty: At the beginning of any problem-solving situation there is a level of uncertainty which pushes us to search for answers and explore related and unrelated situations. Without uncertainty, there would be no need for understanding. Searching and looking for various perspectives help us learn and gain knowledge, and thus get closer to a potential solution. Through the construction of understanding, uncertainty decreases and more positive feelings arise.

Optimism: The more that key aspects and relevant variables are identified, and the pile of useful information starts to grow, the more we feel ready to start solving the problem and we start to experience a positive feeling towards the situation. We focus on objective aspects of the problem and on the information we do know (and have at hand), instead of centering on the parts of the problem we have little knowledge about.

Confusion/Frustration/Doubt: To an optimistic moment in which we achieve clarity on some aspects of the problem, a moment of confusion follows. This happens when we realise the aspects and variables of the problem that still remain uncertain. Consequently, our previous enthusiasm drops. Now what we have thought as understanding is diffused and new doubts emerge.

Clarity: The turning point of the process is when uncertainty feelings decrease and are gradually replaced by strong confidence. This occurs when, through information collected and knowledge gained, we start to make sense of all parts involved in the situation. This allows us to define with more clarity the focus and boundaries of the problem, and see the broader picture too. Then, we are able to evaluate and organise the acquired learning, and put aside the aspects that won’t be useful for this particular problem-situation.

Sense of direction/Confidence: Once we broader our understanding of the problem situation, our confidence and interest increase. In other words, the more clarity we have about the situation we are dealing with, the more confident we feel about the decisions we make and action we choose.

Satisfaction or Disappointment: When we determine an initial solution we experience a feeling of relief. That feeling could be of either satisfaction if we consider that our idea has the potential to evolve into a successful solution, or of disappointment if we aren’t confident enough about the results obtained.

In design, the affective experience often occurs during conceptual design when we are understanding the problem and making sense of the situation. To some extent, we expect to have uncertainty at the beginning of the design process as we are commencing a new challenge. And we frequently experience high levels of uncertainty until we start to define the problem situation with more clarity and identify its complexity, components, and other essential requirements. But, independently of how experienced we are, to achieve understanding, we go through a period of uncertainty. Experience only adds tools to deal smoothly with different unexpected obstacles and feel less overwhelmed during those uncertain moments.

———-

– Kuhlthau, C.C. (1991). Inside the search process: information seeking from the user’s perspective. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 42(5), 361-371.

– Kuhlthau, C.C. (1999). The role of experience in the information search process of an early career information worker: perception of uncertainty, complexity, construction, and sources. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 50(5), 399-412.

Leave a comment